Today we have powerful computers on our desktops, notebooks and tablets in out satchels, bags or rucksacks, and smartphones in our pockets. In 1983 when my software developer career started—I was 15—, I had only a ZX Spectrum home computer (Figure 1) with an 8-bit Z80A CPU, 48K RAM and a separate cassette tape unit—which was the poor man’s hard disk drive that time.

Figure 1: The ZX Spectrum (source: Wikipedia.org)

The father of Spectrum was Sir Clive Sinclair (Figure 2). He’s probably the most famous person in the British home computer industry. God bless him!

Figure 2: Sir Clive Sinclair with his miniature television set in 1981 (source: dailymail.co.uk)

That great computer was an affordable that time with its price around £130. In 1982 my father used the help of a friend who was one of the privileged Hungarians working in West Germany—yes, that time we had two Germanies—and bought me a ZX 81. Almost one year later my father who had seen my enthusiasm for computer programming, collected the necessary amount of Deutsch Mark—the former West German currency—and got me a ZX Spectrum.

In the 80’s we did not have monitors. We used standard TV sets that received analog signals and had to be tuned to a particular TV channel to display the screen. This simple fact leads to a troublesome design aspect of the screen generation, which is one of the hardest challenges when implementing the emulator.

The Architecture of ZX Spectrum 16K/48K

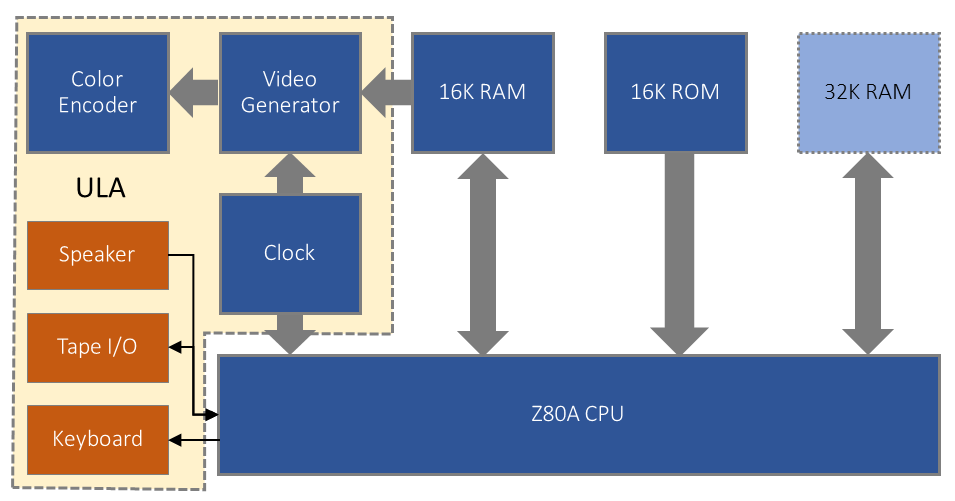

Looking back to the ZX Spectrum’s architecture, you can see that it resembles the computer architectures we use today. Nonetheless, it’s much simpler. Figure 3 shows the simplified blueprint of the machine’s building blocks.

Figure 3: The architecture of Zx Specrum

The CPU

The soul of Spectrum is the Zilog Z80A CPU. In the 1980s, it was one of the cheapest but still powerful microprocessors available in the market. Z80A supports a speed of up to 4MHz, and it can address 64K of memory (with a 16-bit address bus). This CPU became popular both in the industry and among hobbyists, for it has simple interfacing requirements.

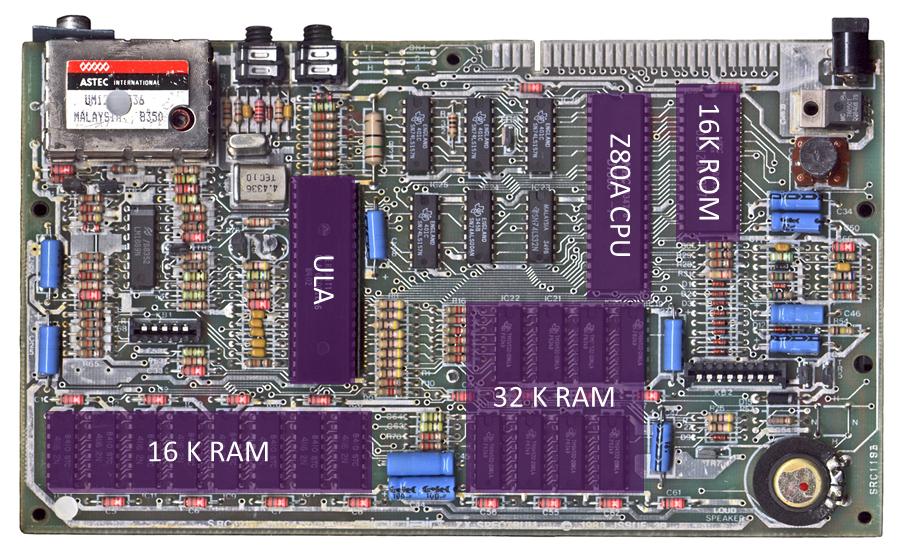

From the 40 pins of the chip (Figure 4), 16 make the address bus (A0-A15), eight of them work as the data bus, two provide the power supply, and one receives the clock signal. All the other pins control the CPU, the bus, the memory or I/O.

The Memory

The operating system of ZX Spectrum is stored in the ROM (Read-Only Memory), which has a size of 16KBytes. I repeat it: 16 Kbytes. How many Linux/Windows/Mac executables do you know that do not exceed this size? The ZX Spectrum ROM contains not only an OS with the ability to manage some peripherals (including a printer!), but also an editor, a BASIC interpreter, a floating-point calculator subsystem, and a character generator bitmap.

When the CPU addresses the range between $0000 and $3fff, it reaches the ROM.

Of course, you need RAM (Random Access Memory) to store dynamic data.

ZX Spectrum initially had two models, the 16K, and 48K models, naming the amount of RAM available. The cheaper model provided RAM for the $4000–$7fff address range, while the more expensive one added extra 32K for the $8000–$ffff range. A part of the lower part of the RAM ($4000–$7fff) was reserved as the video display memory ($4000–$5aff).

Peripherals

It’s not easy to believe that the old ZX Spectrum contained only three simple peripherals: a keyboard matrix with 40 keys (5*8), a speaker controlled with a single bit, and a cassette device with an input (EAR) and an output (MIC).

Figure 4: The motherboard of ZX Spectrum 48K (source: Wikipedia.org)

The ULA Chip

If the CPU was the soul of the machine, another chip, the ULA (Uncommitted Logic Array) was the heart. Besides providing a video display generator, it coordinated the CPU access to memory and peripherals. The ULA chip had a difficult task. Because the electron beam in the cathode-ray tube that used to display the TV-screen that time could not be interrupted, the ULA provided very accurate timing and got priority over the CPU when accessing resources.

Other Spectrum Models

After the release of the first ZX Spectrum model in 1982, Sinclair issued two new models. ZX Spectrum+ (1984) had a new case with an injection-molded keyboard and a reset button. Two years later, Spectrum 128K went to the market (developed in conjunction with the Spanish distributor Investrónica). As its name suggests, this model provided 128K of RAM, with seven 16K banks that could be paged into the $c000–$ffff memory address range. It had two 16K ROMs on two pages that could be paged into the $0000–$3fff range. One of the ROMs was an updated version of the original ZX Spectrum ROM; the other contained a new editor and an extended BASIC interpreter.

Spectrum 128K also had a separate PSG (Programmable Sound Generator), the AY-3-8912 chip, that also provided an RS-232 I/O port.

In 1986, Sinclair sold the Spectrum brand to Amstrad (another British electronics company).

Amstrad’s first release was the ZX Spectrum +2 computer, that was mostly identical to Spectrum 128K. It added a built-in cassette recorder and slightly altered the ROMs. In 1987, two model followed +2, namely +2A and +3 that had four ROMs with floppy disk support. The +3 model had a built-in floppy disk drive.

Since 1984, dozens of official and unofficial clones of the original ZX Spectrum were created. Sinclair licensed the Spectrum design to the USA-based Timex corporation, which created a few new and innovative models.

The countries of the Eastern block (Czech Republic, Russia, Romania, Poland, etc.) have created numerous unofficial clones.

In April 2017, a team of five Spectrum fans (Rick Dickinson, Victor Trucco, Fabio Belavenuto, Jim Bagley, Henrique Olifiers) created a Kickstarter campaign to design and manufacture a new reincarnation named ZX Spectrum Next. They successfully collected more than 700,000 pounds from backers. As of this writing, they have delivered the first developer kits (new motherboards) to backers and work on improving the initial Next model.

The Challenge

When I started the SpectNetIde project, I had a roadmap in my mind, with these milestones:

- ZX Spectrum 48K emulator, tape emulation

- ZX Spectrum 48K emulator integrated with Visual Studio 2017, code discovery and debugging (SpectNetIde)

- Z80 Assembler in Visual Studio 2017, source code debugging support

- ZX Spectrum 128K emulator in SpectNetIde, tooling support updated

Later, as I progressed and got experience, I augmented the roadmap with these items:

- ZX Spectrum +3E emulator with additional tooling support

- ZX Spectrum +3E emulator + floppy drive emulation

- Additional ZX Spectrum development tools (such as Z80 code unit testing)

- ZX Spectrum Next emulation

- ZX Spectrum Next development tools

I successfully managed to leave the first group of milestones behind me, and now, I’m working on the Spectrum +3E emulator.

During the way I’ve been learning a lot. A few things that had seemed straightforward at the beginning went complex. Other things that had looked difficult were not as hard to implement.

In the next few articles, I show you the main challenges I met when implementing the ZX Spectrum 48K emulator. Here is a list of them:

- Emulating and testing the Z80A CPU

- Creating the video display

- Contended memory and I/O

- Generating sound

- Creating a virtual tape device

Stay tuned! Next time I will post an article about Z80A CPU emulation.