CHAPTER 15: More about PRINT and INPUT

Summary

- CLS

- PRINT items: nothing at all

- Expressions (numeric or string type): TAB numeric expression, AT numeric expression, numeric expression**

- PRINT separators: , ; ‘

- INPUT items: variables (numeric or string type)

- LINE string variable

- Any PRINT item not beginning with a letter. (Tokens are not considered as beginning with a letter.)**

- Scrolling

- SCREEN$

You have already seen PRINT used quite a lot, so you will have a rough idea of how it is used. Expressions whose values are printed are called PRINT items, and they are separated by commas or semicolons, which are called PRINT separators. A PRINT item can also be nothing at all, which is a way of explaining what happens when you use two commas in a row.

There are two more kinds of PRINT items, which are used to tell the computer not what, but where to print. For example PRINT AT 11,16;”*“ prints a star in the middle of the screen.

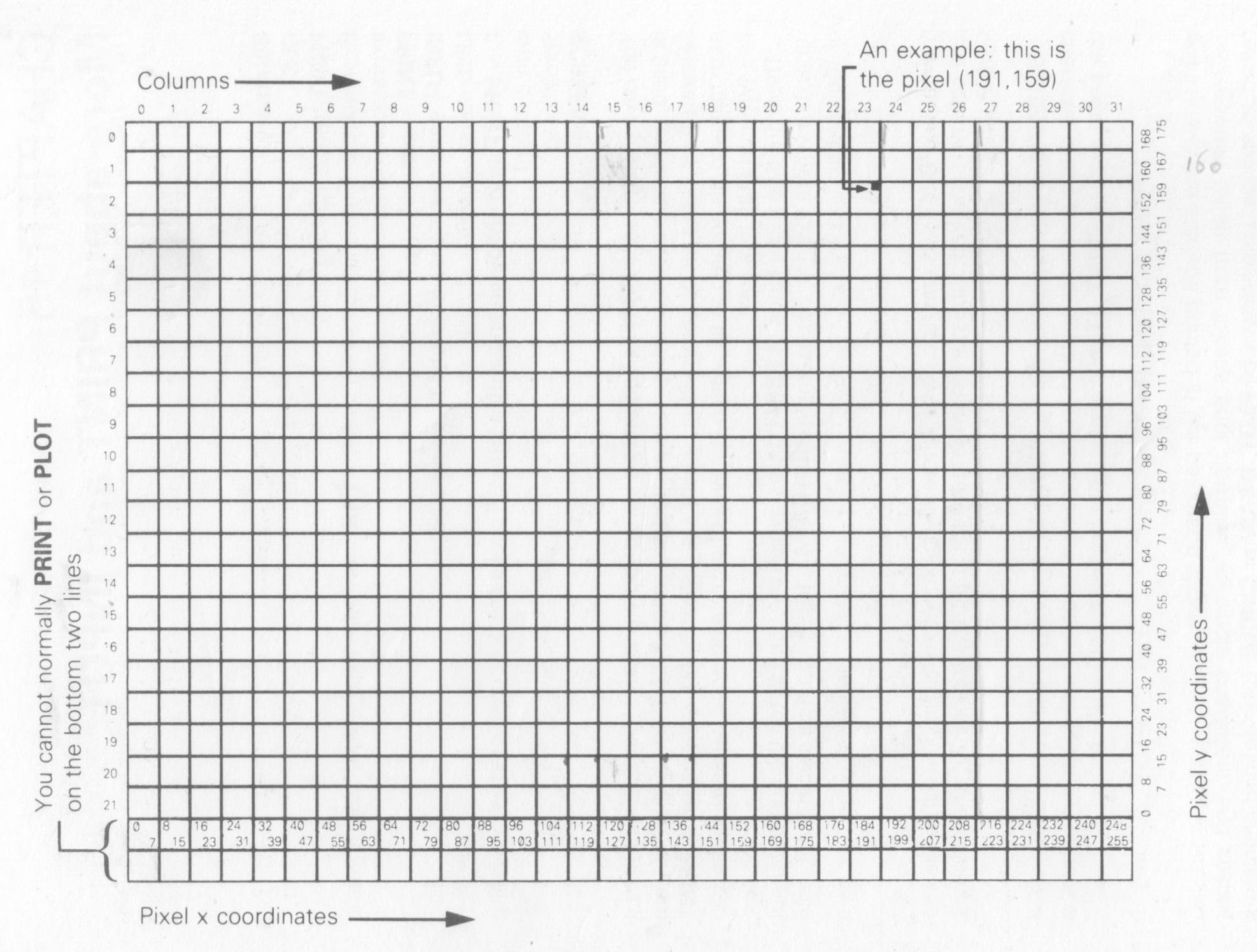

AT line, column

moves the PRINT position (the place where the next item is to be printed) to the line and column specified. Lines are numbered from 0 (at the top) to 21, and columns from 0 (on the left) to 31.

SCREEN$ is the reverse function to PRINT AT, and will tell you (within limits) what character is at a particular position on the screen. It uses line and column numbers in the same way as PRINT AT, but enclosed in brackets: for instance

PRINT SCREEN$ (11,16)

will retrieve the star you printed in the paragraph above.

Characters taken from tokens print normally, as single characters, and spaces return as spaces. Lines drawn by PLOT, DRAW or CIRCLE, user-defined characters and graphics characters return as a null (empty) string, however. The same applies if OVER has been used to create a composite character.

TAB column

prints enough spaces to move the PRINT position to the column specified. It stays on the same line. or, if this would involve backspacing, moves on to the next one. Note that the computer reduces the column number ‘modulo 32’ (it divides by 32 and takes the remainder); so TAB 33 means the same as TAB 1.

As an example,

PRINT TAB 30;1;TAB 12;”Contents”; AT 3,1;”CHAPTER”;TAB 24;”page”

is how you might print out the heading of a contents page on page 1 of a book.

Try running this:

10 FOR n=8 TO 23

20 PRINT TAB 8\*n;n;

30 NEXT n

This shows what is meant by the TAB numbers being reduced modulo 32.

For a more elegant example, change the 8 in line 20 to a 6.

Some small points:

(i): These new items are best terminated with semicolons, as we have done above. You can use commas (or nothing, at the end of the statement), but this means that after having carefully set up the PRINT position you immediately move it on again not usually terribly useful.

(ii): You cannot print on the bottom two lines (22 and 23) on the screen because they are reserved for commands, INPUT data, reports and so on. References to ‘the bottom line’ usually mean line 21.

(iii): You can use AT to put the PRINT position even where there is alreadysomething printed; the old stuff will be obliterated when you print more.

Another statement connected with PRINT is CLS. This clears the whole screen, something that is also done by CLEAR and RUN.

When the printing reaches the bottom of the screen, it starts to scroll upwards rather like a typewriter. You can see this if you do

CLS: FOR n=1 TO 22: PRINT n: NEXT n

and then do

PRINT 99

a few times.

If the computer is printing out reams and reams of stuff, then it takes great care to make sure that nothing is scrolled off the top of the screen until you have had a chance to look at it properly. You can see this happening if you type

CLS: FOR n=1 TO 100: PRINT n: NEXT n

When it has printed a screen full, it will stop, writing scroll? at the bottom of the screen. You can now inspect the first 22 numbers at your leisure. When you have finished with them, press y (for ‘yes’) and the computer will give you another screen full of numbers. Actually, any key will make the computer carry on except n (for ‘no’), STOP (SYMBOL SHIFT and a), or SPACE (the BREAK key). These will make the computer stop running the program with a report D BREAK - CONT repeats.

The INPUT statement can do much more than we have told you so far. You have already seen INPUT statements like

INPUT “How old are you?”, age

in which the computer prints the caption How old are you? at the bottom of the screen, and then you have to type in your age.

In fact, an INPUT statement is made up of items and separators in exactly the same way as a PRINT statement is, so How old are you? and age are both INPUT items. INPUT items are generally the same as PRINT items, but there are some very important differences.

First, an obvious extra INPUT item is the variable whose value you are to type in age in our example above. The rule is that if an INPUT item begins with a letter, it must be a variable whose value is to be input.

Second, this would seem to mean that you can’t print out the values of variables as part of a caption; however, you can get round this by putting brackets round the variable. Any expression that starts with a letter must be enclosed in brackets if it is to be printed as part of a caption.

Any kind of PRINT item that is not affected by these rules is also an INPUT item. Here is an example to illustrate what’s going on:

LET my age = **INT (RND * 100): INPUT (“I am “;my age; “. “);”How old are you?”, your age**

my age is contained in brackets, so its value gets printed out. your age is not contained in brackets, so you have to type its value in.

Everything that an INPUT statement writes goes to the bottom part of the screen, which acts somewhat independently of the top half. In particular, its lines are numbered relative to the top line of the bottom half, even if this has moved up the actual television screen (which it does if you type lots and lots of INPUT data).

To see how AT works in INPUT statements, try running this:

10 INPUT “This is line 1.”,a$; AT 0,0;”This is line 0.”,a$; AT 2,0;

“This is line 2.”,a$; AT 1,0; “This is still line 1.”,a$

(just press ENTER each time it stops.) When This is line 2. is printed, the lower part of the screen moves up to make room for it; but the numbering moves up as well, so that the lines of text keep their same numbers.

Now try this:

10 FOR n=0 TO 19: PRINT AT n,0;n;: NEXT n

20 **INPUT** AT 0,0;a$; AT 1,0;a$; AT 2,0;a$; AT 3,0;a$; AT 4,0;a$; AT

5,0;a$;

As the lower part of the screen goes up and up, the upper part is undisturbed until the lower part threatens to write on the same line as the PRINT position. Then the upper part starts scrolling up to avoid this.

Another refinement to the INPUT statement that we haven’t seen yet is called LINE input and is a different way of inputting string variables. If you write LINE before the name of a string variable to be input, as in

INPUT LINE a$

then the computer will not give you the string quotes that it normally does for a string variable, although it will pretend to itself that they are there. So if you type in

cat

as the INPUT data, a$ will be given the value cat. Because the string quotes do not appear on the string, you cannot delete them and type in a different sort of string expression for the INPUT data. Remember that you cannot use LINE for numeric variables.

The control characters CHR$ Z and CHR$ 23 have effects rather like AT and TAB. They are rather odd as control characters, because whenever one is sent to the television to be printed, it must be followed by two more characters that do not have their usual effect: they are treated as numbers (their codes) to specify the line and column (for AT) or the tab position (for TAB). You will almost always find it easier to use AT and TAB in the usual way rather than the control characters, but they might be useful in some circumstances. The AT control character is CHR$ 22. The first character after it specifies the line number and the second the column number, so that

PRINT CHR$ 22+CHR$ 1 +CHR$ c;

has exactly the same effect as

PRINT AT 1,c;

This is so even if CHR$ 1 or CHR$ c would normally have a different meaning (for instance if c=13); the CHR$ 22 before them overrides that.

The TAB control character is CHR$ 23 and the two characters after it are used to give a number between 0 and 65535 specifying the number you would have in a TAB item:

PRINT CHRS 23+CHRS a+CHRS b;

has the same effect as

PRINT TAB a+256*b;

You can use POKE to stop the computer asking you scroll? by doing

POKE 23692,255

every so often. After this it will scroll up 255 times before stopping with scroll?. As an example, try

10 FOR n=0 TO 10000

20 PRINT n: POKE 23692,255

30 NEXT n

and watch everything whizz off the screen!

Exercises

- Try this program on some children, to test their multiplication tables.

10 LET m$=" "

20 LET a=INT (RND*12)+1: LET b=lNT (RND*12)+1

30 INPUT (m$) ' ' "what is ";(a) ";(b);"?";c

100 IF c=a-b THEN LET m$="Right.": GO TO 20

110 LET m$=''Wrong. Try again.": GO TO 30

If they are perceptive, they might manage to work out that they do not have to do the calculation themselves. For instance, if the computer asks them to type the answer to 2*3, all they have to type in is 2*3.

One way of getting round this is to make them input strings instead of numbers. Replace c in line 30 by c$. and in line 100 by VAL c$, and insert a line

40 IF c$ <> STR$ **VAL** c$ THEN LET m$="Type it properly, as a number,":GO TO 30

That will fool them. After a few more days, however, one of them may discover that they can get round this by rubbing out the string quotes and typing in STR$ (2*3). To stop up this loophole, you can replace c$ in line 30 by LINE c$.